I have recently been in charge of implementing a Configuration Management tool. A Configuration Management tool, simply put, allows automation and management of configuration, usually for Virtual Machines. This helps to scale and maintain consistency and speeds up setup considerably.

While my team is developing a Kubernetes-based platform and the focus continues to be on Kubernetes and Cloud Native, there is still a need for Virtual Machines. So, of course, these VMs need correct and scalable configuration management.

Puppet and Ansible are two prominent offerings for Configuration Management, and I had previously never worked with either. To evaluate them, I decided to blog about them at an introductory level!

In this first post of a series, I hope to describe:

- Basics about Ansible

- Some examples

- What use cases the tools suit best.

- Wether or not Ansible is fit for purpose

I will only cover Ansible’s open-source (e.g., Free) offerings. This is also not intended as a tutorial, just my first impressions and thoughts surrounding this tool; expect a deeper dive later.

NOTE: This post only focuses on Ansible; I will explore Puppet later.

Why even Puppet or Ansible?

The engineers on the customer side already have experience with Puppet, which has been around since 2009.

I have yet to gain any experience with the Puppet tool, but I know of the organization through the State of DevOps Report, which they co-author annually. Well worth the read.

On the other hand, the organization I work in has largely standardized around Ansible. It is viewed by many as a de facto standard for Configuration Management in the cloud, even if it is younger than Puppet. Ansible was initially released in 2012; by 2015, it was acquired by Red Hat.

Regarding market share, I found this report from JetBrains from back in 2019, which claimed that Ansible has a share of 23%, contrary to Puppets’ share of just 9%, but this does not necessarily provide the complete picture. Paid reports, such as from Gartner, may have completely different findings.

If you have some insight or other sources, please go ahead and leave a comment.

Requirements

Ideally, the setup to make Configuration Management available for a team must be minimal and deadly simple.

I *am* lazy, but that is not the only reason for this requirement.

The organization we work with is enormous, and we can’t follow up with every team that will use the Platform.

Scalability and efficiency are essential criteria.

My team is mandated as a platform team, meaning that we enable the efficient and safe use of a Platform. We are not, however, an operations team. In other words, the consumers will be wholly responsible for how and when to use the Platform – within the boundaries and guardrails we set up for them.

In summary, these are the essential requirements for my use case:

- Ease of use

- Ease of deployment

- Scalability

- Access Controls and Multi-tenancy

Ansible

Ansible was very easy to get into. By using the quickstart over at Getting started with Ansible — Ansible Documentation, I was quickly able to get started.

Ansible does just what it says on the tin. It automates the management of remote systems and makes sure they uphold the desired state we have declared.

Ansible uses so-called playbooks (files) consisting of plays, optional roles and tasks. Modules contain the primary logic for accomplishing what is defined in those tasks.

The plays and tasks in a playbook is executed sequentially, meaning that we can have code written last execute, well, last.

For writing the actual code, Ansible uses good old YAML and there is a very good extension in Visual Studio Code that makes writing code pretty seamless.

Architecture

Ansible is agentless, which means that management is done through native mechanisms such as SSH or WinRM.

It still needs a dedicated primary node on which Ansible playbooks are executed, and that is responsible for pushing configuration to the managed nodes.

The primary node needs to run Unix and Python 3.9 or newer, but other than that there is no requirements.

The managed nodes don’t need Ansible installed, but they need a compatible version of python to execute the code that Ansible deploys.

Since my lab is running Ubuntu, this was no issue. Python came pre-installed on all my VMs.

I quite like the agentless approach. This means that adding nodes to management is very quick and seamless. In most cases, this makes use of methods that already exist in the environment that is going to be managed.

This also means that management is push-based. The primary ansible node need to execute a command to push configuration to managed nodes, there is no mechanism on the nodes to pull config.

That is kinda “meh”. This means a node can drift or fall out of configuration and remain in a non-compliant state until ansible pushes configuration (if needed) again. Such as a developer “just debuging their application on a server”.

I imagine there are ways around that, if necessary. I have not looked into doing this pull-based, but you can probably run cronjobs or similar. I don’t know. (maybe you do? The comment section is down below 👇)

Getting started with Ansible

Since python and pip came pre-installed with all the nodes i were testing on, i only needed to run this command on the primary node:

python3 -m pip install --upgrade --user ansible

After installation i could start creating playbooks and inventory anywhere i wanted.

Inventory files are an “inventory” of the hosts to be managed, and in my case it looked like this.

# ~/ansible/inventory.yaml

#Group labb

labb:

hosts:

lin-0:

ansible_host: lin-0

lin-1:

ansible_host: lin-1

I started of by testing a simple hello world, as described in the quickstart.

# ~/ansible/welcome_play.yaml

- name: welcome play

hosts: labb

tasks:

- name: Ping

ansible.builtin.ping:

- name: Print

ansible.builtin.debug:

msg: hey hey

This simple hello world make use of two builtin ansible modules.

- ansible.builtin.ping

- does a mock ICMP ping, to verify that ansible can reach a managed node.

- ansible.builtin.debug

- prints output to terminal

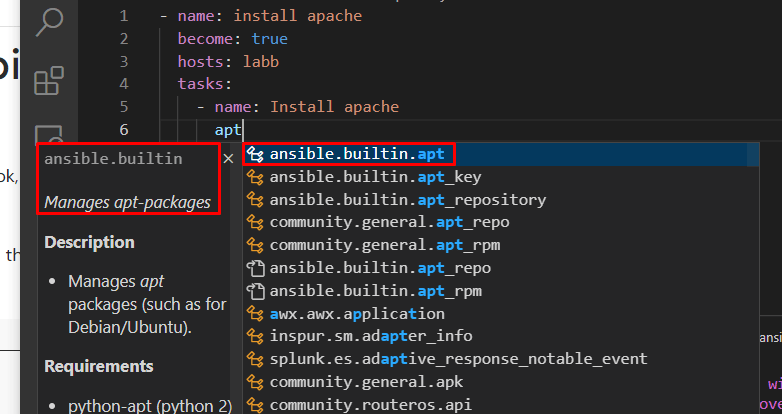

The VSCode extension help understanding these modules:

I really like the clarity that the extension for VSCode provides, writing the ansible playbook felt really simple and documentation was very close.

Now, to actually execute the ansible code i ran this command:

ansible-playbook -i inventory.yaml welcome_play.yaml

The -i flag defines what inventory file to use, while welcome_play.yaml is the runbook to execute. Both these files can be named whatever we want.

Outputing this:

PLAY [welcome play] ********************************************************************

TASK [Gathering Facts] *****************************************************************

ok: [lin-0]

ok: [lin-1]

TASK [Ping] ****************************************************************************

ok: [lin-1]

ok: [lin-0]

TASK [Print] ***************************************************************************

ok: [lin-0] => {

"msg": "hey hey"

}

ok: [lin-1] => {

"msg": "hey hey"

}

PLAY RECAP *****************************************************************************

lin-0 : ok=3 changed=0 unreachable=0 failed=0 skipped=0 rescued=0 ignored=0

lin-1 : ok=3 changed=0 unreachable=0 failed=0 skipped=0 rescued=0 ignored=0

The output here is very human-readable, it’s easy to distinguish the result and what tasks were executed. Remember, a playbook contains one or more plays, again containing one or more tasks.

The way I understood this is that plays will define which hosts to run the underlying tasks against. Tasks, on the other hand, are only calls to modules. Modules are the actual code that will be executed to accomplish the goal.

Exploring Ansible a bit further

Okay, that was a straightforward playbook; how about creating a playbook for a more “real” use case?

I attempted to set up apache2 on my servers, and the playbook worked on my first try:

- name: install apache

become: true

hosts: labb

tasks:

- name: Install apache

ansible.builtin.apt:

name: apache2

state: latest

I did not need to check the Ansible documentation for this, the extension VScode did all the magic. I just entered “apt”, and it suggested the module for me.

Okay, now we had created a simple task, how about bringing it even further? making the use-case “real”.

We want apache2 installed, but it should only be running if it is currently a Wednesday!

- name: install apache

become: true

hosts: labb

tasks:

- name: Install apache

ansible.builtin.apt

name: apache2

state: latest

- name: ensure apache is running

ansible.builtin.service:

name: apache2

state: started

when: ansible_date_time.weekday == "Wednesday"

- name: ensure apache is not running

ansible.builtin.service:

name: apache2

state: stopped

when: ansible_date_time.weekday != "Wednesday"

So, the intent was to test a simple conditional here. The Keyword “when” does the trick, allowing us to execute some tasks conditionally. Here, the task triggers depending on the ansible_date_time.weekday variable being equal to “Wednesday.” This, by the way, is one of the many built-in variables we can source when using Ansible.

So far, writing playbooks in Ansible feels intuitive and straightforward. These examples combined with functionality like targeting hosts by patterns and YAML Anchors or aliases, make Ansible feel very capable.

Use Cases for Ansible

Ansible is helpful for dynamic environments such as cloud environments, partly due to its inventory feature. As Ansible doesn’t require any agents to be installed, it should be ready for any virtual machine as long as SSH or WINRM is configured and Ansible is provided with credentials.

Another prime use case is for the initial configuration of servers. Virtual Machines, in particular, can benefit significantly from Ansible’s speed.

Ansible can be dependent on a lot of modules provided by the community. Therefore, it may not be the best fit for air-gapped environments or environments with limited internet access. Of course, Ansible is still possible and often still preferred to use, but required packages and modules would need to be downloaded for offline usage in advance.

What Ansible is not

While I have highlighted many of the benefits of Ansible, I should mention that Ansible provides no API, access control, or GUI for running these playbooks. Ansible is simply a command line tool that can be executed from your terminal or pipeline.

This means that you would also need to look into another tool to provide those features, with access control being the key missing feature for us.

On another post, i will therefore look into Ansible AWX, the upstream and open source version of Red Hat Ansible Automation Platform. This is an automation engine and GUI expanding on Ansible.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I had a great experience learning and getting into Ansible. I was positively surprised by how easy it was to get going. The community around Ansible is thriving, and developing was pretty seamless by using premade modules and the Visual Studio Code Extension.

Ansible is very much fit for purpose, but, as mentioned in the previous paragraph, ansible itself is just a command line tool that comes without an automated task engine, GUI or Access controls. Thats why using Ansible AWX is the logical next step. Stay tuned for my post about this!

Leave a comment